Both the Arawak and Carib tribes made periodic visits to St Barth, but the first group of approximately 50 French settlers didn’t come to the island until 1648.

In the beginning of the Christian era, the Arawaks, a tribe from Venezuela, made their first appearance in the Antilles archipelago. Agriculturists and pacifists, they were massacred in the 12th century by the Caribs. As a result of bloody battles, the Arawaks disappeared definitively over time. Perhaps it was due to the lack of fresh water or the inhospitable topography of the island, but the Caribs never lived permanently in Saint Barth. They did however baptize the island Ouanalao (pelican) and established temporary encampments. Traces of their visits were found during the construction of the Gustave III airport in St Jean.

St Barth remained virtually unknown until 1493, when it is believed that Christopher Columbus discovered the island on his second voyage to the West Indies, and named it after his brother Bartholomew. The Spanish did not settle on the island and the years went by… until the 17th century, when the French, English, and Spanish sought to rule the Caribbean islands. They fought over ownership with cannons, and each nation desired to establish a stronghold as quickly as possible to confirm their colonial presence. According to reports from that period in time, it was in 1648 that the first colony of 40 people arrived. They had names such as Laplace, Danet, Magras, Aubin, Lédée, Questel, Bernier, Blanchard, and Gréaux. These French settlers came from Normandy, Bordeaux, Brittany, or the South of France, seeking their fortune in the West Indies. They met up with pirates who used the sheltered harbor of Gustavia (called Carénage at that time) as a discreet refuge.

A peaceful co-existence lasted until 1656, when the bellicose Caribs attacked the island and massacred the settlers. The result of this carnage meant that St Barth remained

In 1784, Louis XVI negotiated with Swedish king Gustave III, to exchange the island for a commercial base consisting of warehouses in Gothenburg, Sweden. At that time, St Barth was declared a “free port,” a decision that opened the door to a period of prosperity that lasted until 1813 when the island’s fortunes began to decline. Commercial competition from neighboring islands, and recurring catastrophic weather conditions convinced Sweden to propose the retrocession of St Barth to France. A treaty was signed on March 15, 1878 and once again the French flag flew over this tiny jewel of just nine square miles.

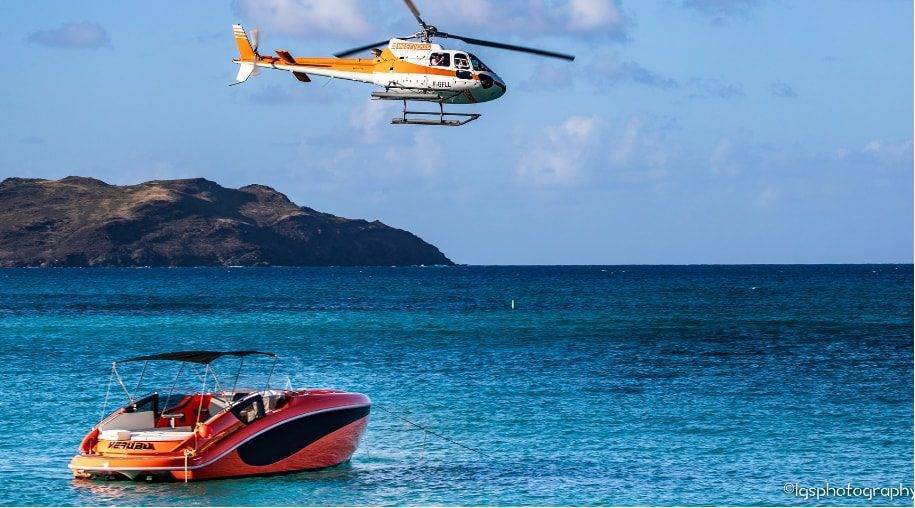

A hundred years later, St Barth began to develop into one of the most extraordinary tourist destinations in the world, preserving its natural beauty, its fabulous white-sand beaches, and cultural authenticity, while at the same time offering luxury hotels for an exclusive clientele. Its status as a free port is one of its assets, along with restaurants serving fine French cuisine with Creole accents, a range of nautical activities, and shopping from haute couture to young designers. It all adds up to a safe, desirable destination far from the expected.

© Histoire de St-Barth aux éditions du Latanier